Victor Hugo’s Drawings

A multi-faceted genius, Victor Hugo was one of the greatest drawing artists of his era. His drawings, which were initially kept private and secret, have today taken their place in the pantheon of art. The museum holds the most significant collection of this body of work, which is one of the most unique and modern produced in its time.

The initial core of the collection was built up by Paul Meurice from three sources: his own collection, the family collection and Juliette Drouet’s drawings. He acquired the latter from his nephew, Louis Koch. Since then, the collection has been continuously enriched through purchases and donations, and now comprises more than 700 items. It provides an insight into practically all aspects of Victor Hugo's visual artwork. It is particularly rich in drawings that were truly intended to be hung on the wall, sometimes in frames painted by Hugo himself. It includes some of the master’s greatest and most famous drawings.

Drawing was part of Victor Hugo's education, but it was not until the early 1830s that he produced caricatures with a sharp and witty pen for his own pleasure and to amuse his friends and family. From 1834, he would regularly fill his travel journals with drawings, usually in pencil, to remind him of places or architectural details. On reaching his destination, he would copy them in ink to send to his children, who were delighted with them. His trips to the Rhine Valley in 1839 and 1840 left their mark on his imagination. The sight of the burgs on the mountainous riverbanks provided lasting inspiration for his work.

Around 1847 Victor Hugo reached full mastery of his art, creating his own technique of mixing lithographic crayon with charcoal and ink wash. At the end of summer 1850, he set up an actual studio in Juliette Drouet's dining room. Once he was caught up in politics and hardly wrote at all, his creative fever was given free rein in a series of large-scale drawings, with unbridled vision and deep, tormented resonance: Le Burg à la Croix [Fortress with the Crucifix], Le Champignon [Mushroom], Gallia, La Ville morte [The Dead City], Vue de Paris [View of Paris], Paysage aux trois arbres [The Three Trees], etc. Victor Hugo increased his technical experimentation, using a soluble screen for a cracking effect, blending inks and gouache, using a variety of materials, scraping, etc., all with the aim of adding dramaturgy to his drawing. He also used inkblots as prompts to his imagination in a way that would later fascinate Surrealists. As a result his drawings are considered modern.

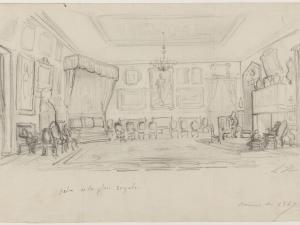

His years of exile were an intense period of creativity in terms of artwork, with fantastical drawings imbued with his experience of Jersey seance tables, and numerous seascapes with radiant skies. Victor Hugo's great struggle against the death penalty was expressed in several masterpieces such as “the Hanged Men”, Ecce and Ecce Lex. Physical distance was also the reason why he developed a habit of sending “greeting cards” (drawings in which Hugo played with the calligraphy of his name). Several examples are held in the museum. Once he settled on Guernsey, Hugo developed this new vein. The use of stencils or screens cut out of paper, lace or leaf prints is particularly characteristic of this period. The refurbishment of Hauteville House resulted in numerous sketches for furniture and décor. Hugo also gave those around him picture frames he had painted himself, such as for the "Souvenirs” series that were to be hung on the walls of the Billiard Room. The museum has preserved the majority of these.

Hugo sometimes gave artistic expression to his literary creations or, to be more accurate, pursued his vision on two fronts. This is the case for Toilers of the Sea and The Man Who Laughs with Eddystone Lighthouse and Casquets Lighthouse. Among later works begun at the end of exile, the images that tell the story of the Poème de la sorcière [The Witch], stand out in the collection. This set of grotesque faces by Hugo seem reminiscent of Goya, in a new plea against cruel, blind justice.

Hugo also left behind a number of inkblots, which we have begun to look at in a new way. Were they simple technical tests or early creative steps, awaiting an interpretation that would “extend their meaning” (in the words of André Masson)? Their quality and richness were admired by the Surrealists and by many 20th century artists who saw in them the beginnings of automatism and abstraction.